How Do Insects Cope With The Cold at Bethpage State Park!? Here is Insect Survival Tactics 101 - Winter Edition!

Between whiteout conditions and flurries this month, the courses remain frozen and Bethpage State Park feels a little less active this time of year. This is not just because of the lack of golf-playing; I'm actually referring to the wildlife too! While many of you know that some birds migrate South and mammals hibernate...have you ever wondered what insects are up to during the winter season? Where do they go? What do they do? How in the world do they survive frigid cold temperatures?

Well, to make this answer even more mysterious and complex, insects are considered the most diverse group of animals on Earth. Whether it is their unique adaptions or how they utilize resources, each species behaves in their own way and their means for survival varies! However, one thing that ALL insects have in common is the fact that that they are cold-blooded. Not in the literal sense, but more so that their internal temperature is in accordance with the temperature of their surroundings. Scientists call these organisms poikilotherms (a word that derives from ancient Greek words poikilo, meaning variable and therm meaning warmth). As you can imagine, this quality means that insects have to take quick action before/during the winter, to ensure they and/or their future generations are protected from what lies ahead!

|

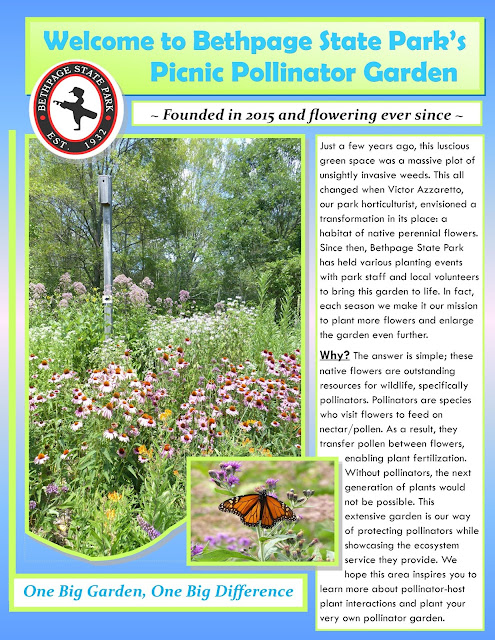

| Monarchs feed on nectar in our garden before their big journey to Mexico. |

Lets start the discussion with the insect that goes the furthest to avoid winter...the monarch butterfly. Similar to birds, monarchs will migrate south, specifically to the mountaintop forests of Mexico. What is most outstanding about this journey is that this is the only butterfly migration up to 3,000 miles long. It also takes multiple monarch generations to complete (meaning a butterfly that leaves New York can be an ancestor of a butterfly that returns come springtime)! At the Mexican overwintering sites, monarchs create massive roosts on the trunks of the oyamel fir trees. These trees, growing in humid and high altitude locations, provide the perfect micro-climate; that is, a habitat that is cold enough for the monarchs to lower their metabolism and reserve energy for their flight back home, yet still warm enough for them to bask in the sun and not freeze to death (which would surely happen if they stayed in NY at 20 degrees and below). This inactive state, similar to hibernation is called diapause. You might be wondering why monarchs even bother flying back North after winter ends? Well, it is because as caterpillars, they rely only on the milkweed plant. This is a type of wildflower native to the U.S. but not abundant at their winter roost sites. That alone, is one of the main reasons we work so hard at Bethpage State Park to create pollinator gardens and protect wild, milkweed patches along our fairways.

Last October, Golf Course Superintendent

Erik found this Hornworm digging into our turf.

|

|

| Winter cluster of honeybees in our hive box on the Black Course. |

Moira prepared a "sugar cake" for our honeybees, increasing the odds of successful spring hives!

Although, not all insects are like the honey bee; many do not have the advantage of communal living. In fact, many adult insect generations die off during the winter months, but before they go, they invest energy and time into ensuring their young make it through wintry conditions. One insect that does this is the praying mantis! The female praying mantis will stick around long enough to lay hundreds of eggs. These eggs are covered with a liquid that hardens to become a protective casing. This case structure is called an ootheca, and is strong enough to withstand the cold and most predators. Oothecae can be seen on bare branches, fences, and even on the siding of some buildings. Within the ootheca, some mantis nymphs will practice cannibalism, eating their siblings for nutrients (this seems very different from the honeybee teamwork in the hive!). When warm weather and the promise of other food arrives, the nymphs will say goodbye to their winter home and disperse from the casing!

|

| This praying mantis ootheca was found on a tree branch, near the pollinator garden, on the Green Course . |

Regardless of whether they stay or leave, the lengths at which insects will go to survive the hardships of winter is perhaps the most resourceful of all the animal kingdom! Knowing their adaptations and efforts makes it even more outstanding to see them pop up again come springtime. It also reiterates our responsibility to ensure insects have sustainable shelters and bountiful forage opportunities (i.e. pollinator gardens) all throughout summer and even fall...this way, our insect populations will have the energy means to do it all over again next winter!

Comments

Post a Comment